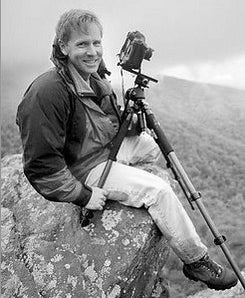

Marc Muench (www.muenchphotography.com) has been a professional landscape and sports photographer for over 20 years. Marc is now the "artist in residence" at dgrin.com for Smugmug, where he contributes on a regular basis to the "Muench University" critique thread. He is currently the photo editor of the National Parks guide, published by The American Park Network, which contain many of his images taken throughout the United States National Park system. We asked Marc to share some information about the Tilt Shift lenses and how to use them for landscape photography. Marc's personalized attention in his workshops will give you even more confidence in testing out some of these principles.

Marc: "The Tilt-Shift lens for dSLRs is strange variation on the normal lens by providing photographers, especially those who shoot architecture, landscape, or generally wide angles to correct for parallax distortion, to increase the depth of focus, and to provide selective focus. A photographer may find other ways to accomplish these objectives, but they are often more cumbersome (such as shooting large format film) or using cheaper tools that may degrade the quality of image (like a Lensbaby). There are many "workarounds" for achieving these goals, and in fact, a Lensbaby may be a very affordable alternative to the more expensive Tilt-Shift lens, and may even produce a greater effect. There are pros and cons to each method of approaching a problem in photography, and here we will show what a Tilt-Shift lens can provide your photography.

THE "SHIFT"

"Each lens is provided with several small knobs, the closest one to the camera being the "shift" function. Twist it and the lens moves up and down relative to the plane of the sensor (or film). Effectively, this corrects the converging lines in the top portion of the frame, of say, the edges of a building. If I were to point my camera directly upwards with a fixed 20 mm lens, this distortion would becomes very obvious. In fact, the only way to keep the parallel lines at the top of a building would be either to raise myself up to an altitude where I was directly facing the building (perhaps on an adjacent building) or correct this parallax problem by shifting my lens upward in relation to the plane of the sensor. Adjusting this usually requires a repositioning of the camera itself while you shifting the lens, and you will find that you do not need to point the camera as high upwards with the lens shifted as you needed to do when it was not shifted.

This entire process allows the photographer to stand closer to the building and still retain the "straightness" of the lines. In effect, you can imagine that this also works very well shooting interior photography when the photographer can't sometimes include a very high vaulted ceiling realistically. Simply shift the lens upwards and recompose. Note that especially with interiors and often for exteriors, the photographer is close enough to the subject that a wide angle lens is necessary. Canon's 24 mm TS II (Tilt-Shift) lens and its new 17 mm TS II (Tilt-Shift) make up the newest line of excellent glass for these photographers. Landscape photographers jump right in too when the trees in an image suddenly exhibit the same problem. The most common move with a large format camera while creating landscape images is to shift down, then tilt the plane of focus. These two move allow little if no distortion to verticals and creates a plane of focus allowing the very near foreground and the very distant horizon to be in focus at a wider aperture than normal. For example, I usually utilize an aperture of f/11, providing I have correctly made the tilt move.

THE "TILT"

"The knob closer to the front of the lens usually "tilts" the front of a Tilt-Shift lens, which means that the plane of the lens is not parallel to the plane of the sensor or piece of film. This can do some amazing things, the first of which you will immediately notice is that it creates a similar effect to a Lensbaby, a cheaper way to achieve a selective focus or tilt.

"Since I work mainly outdoors, I try to use the Scheimplug Principle when I am shooting with a Tilt-Shift lens. This type of lens is the only way to produce a different plane of focus that replicates the old bellows of large format film cameras. Essentially, the front aspect of the lens tilted downwards and at a certain point, the plane of focus begins in front of the photographer and travels to infinity along a plane that is closer to parallel with the ground. This is an advanced technique for getting a sharper focus front to back in a landscape image and requires some practice. Because these lenses are manual focus, the photographer can use the focal points to light up different areas of the scene to see if the camera agrees they are in focus. Newer models will give off the focus chirp at each point that is in the focal plane, making it very useful for landscape photographers.

"My personal protocol for this procedure is:

- Find composition with lens completely zeroed out, no tilt or shift

- With camera in Manual mode, set aperture and proper shutter speed

- Move camera into position by making level with live view "level tool"

- Shift down to reach original composition

- Make a one degree tilt

- With live view active, zoom in to 5x and check focus on foreground

- Scroll around in live view to check focus on background

- Re-focus to position where both FG and BG are as close to focus as possible

- Make another ½ or 1 degree tilt

- Finally check focus on FG and BG and adjust focus until just right

"I normally don’t tilt beyond 2 ½ degrees. And don’t forget, the reason this is so very important is that these lenses are sharper at f/11!"

RELATED ARTICLES

How I Got That Shot - Royce Bair Shooting Nightscapes

Shawn Reeder's Yosemite Time Lapse

How I Got That Shot - Jack Dykinga in the Sonoran Desert